This 1967 statement, probably wrongly attributed to U.S. Surgeon General Dr. William H. Stewart, reflects the euphoria of a time when, thanks to the rapid development of highly effective antibiotics, the treatment of bacterial infections was regularly so successful that infectious diseases were thought to have been defeated. In the years before, numerous new active substances such as penicillins, tetracyclines, cephalosporins and macrolides had been introduced into clinical medicine and further pharmaceutical “miracle weapons”, above all fluoroquinolones and carbapenems, were to follow. Even though the first resistant bacterial strains were soon reported for each substance class, the “cornucopia” of the pharmaceutical industry seemed to be immeasurably large. Reminders to deal with these substances rationally – prudently – were obviously just as little regarded as the observance of important hygiene rules, whose consistent application can effectively prevent the spread of pathogens in the hospital environment.

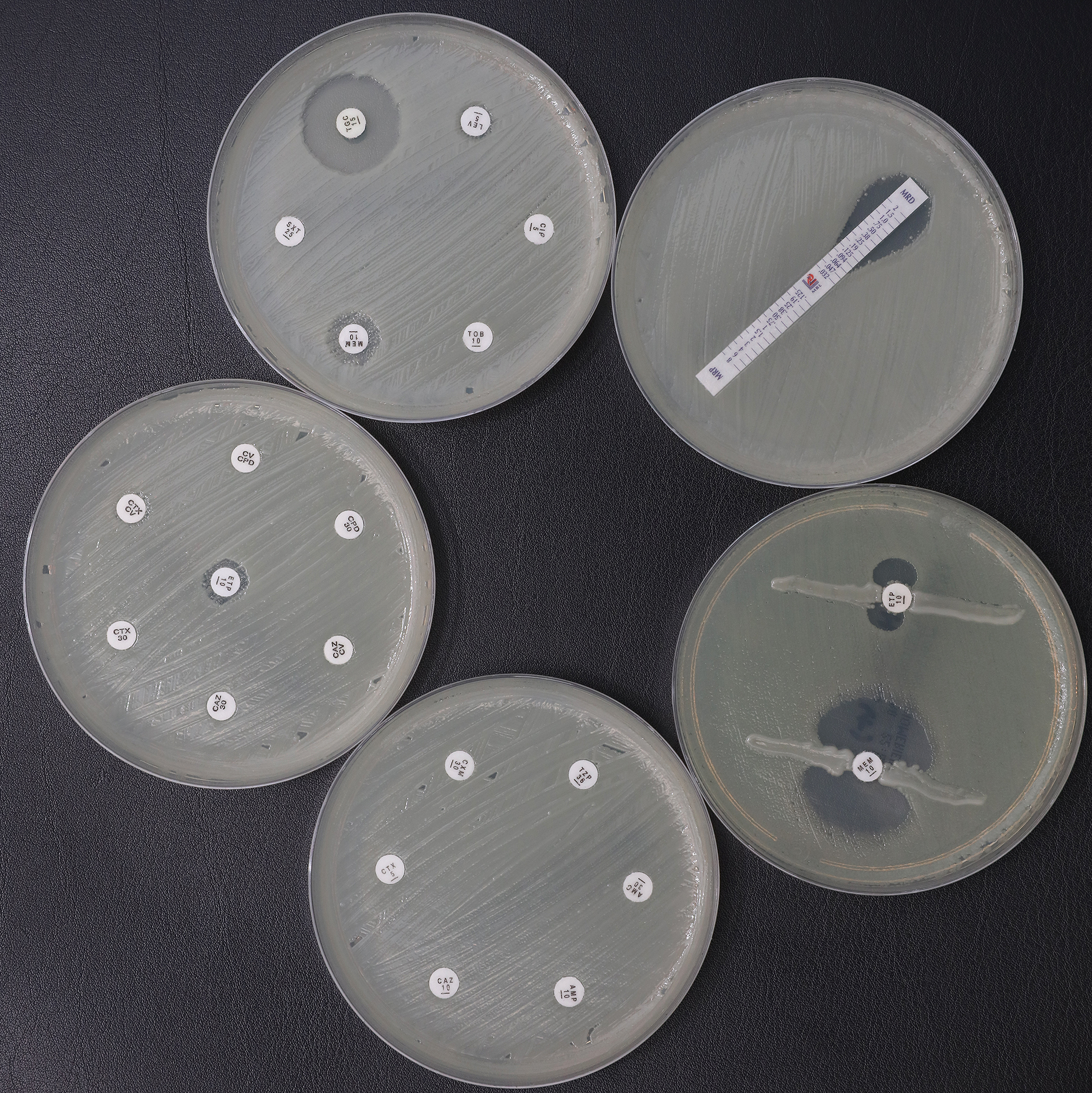

In the mid-nineties of the last century, alarming epidemiological data in Germany and many other countries led to a radical rethink in the handling of clinically relevant microorganisms. The bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, the cause of numerous serious diseases such as sepsis, infectious endocarditis, pneumonia or wound and soft tissue infections, showed increasing non-susceptibility to penicillin preparations for the treatment of particularly resistant bacteria of this type. To date, considerable health policy efforts have been required to address the problem of the spread of these methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains, which are always resistant to a variety of antibiotics. This includes, in particular, special treatment measures, including isolation of patients in single rooms, cost-intensive laboratory tests and the development of new drugs.

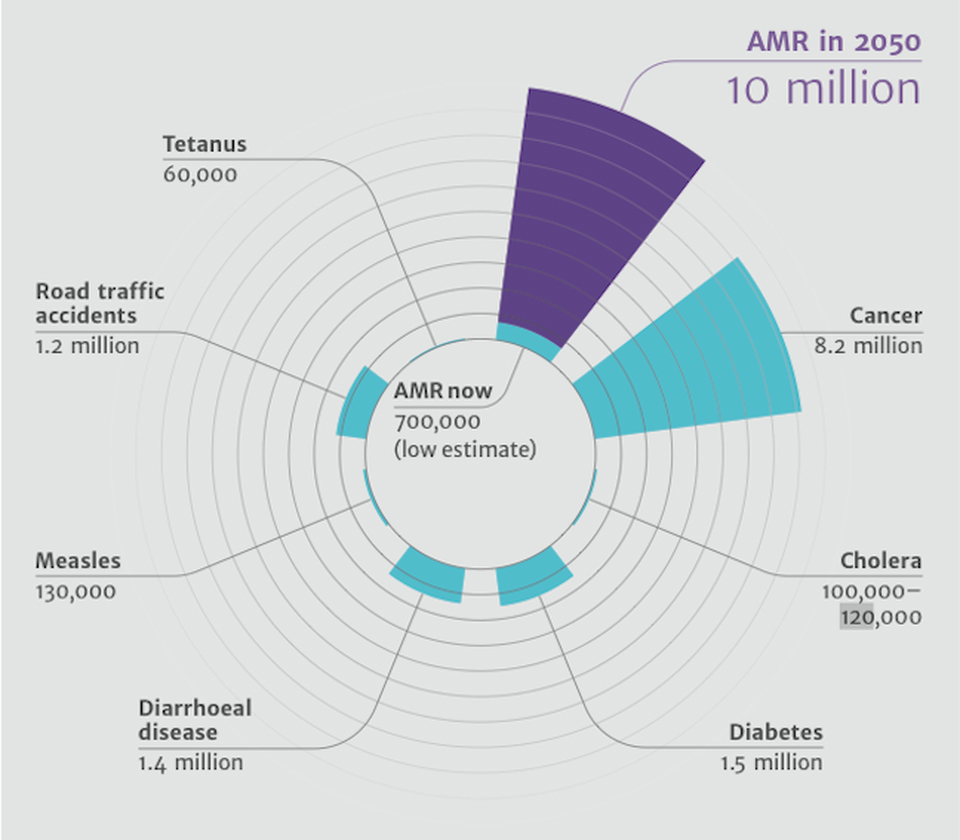

The causes for the increasing spread of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) are manifold. Decades of misuse and overuse of antibiotics in human and veterinary medicine are of crucial importance. The widespread use of antimicrobial substances in animal production, the uncontrolled discharge of wastewater containing antibiotics into the environment, the inadequate application of antibacterial drugs for the treatment of colds and other banal viral diseases, and the uncritical “over the counter” sale of these drugs in countries with underdeveloped health care systems, combined with the distribution opportunities offered by international travel, have developed into one of the greatest health policy challenges of our time. Estimates by a British commission of experts in 2016 suggest that around 10 million people worldwide could die in 2050 from an infection caused by a multi-drug-resistant pathogen. This could mean more deaths than through cancer. Last but not least, the World Health Organization (WHO) is addressing the threat of the post-antibiotic age and calls for immediate action.

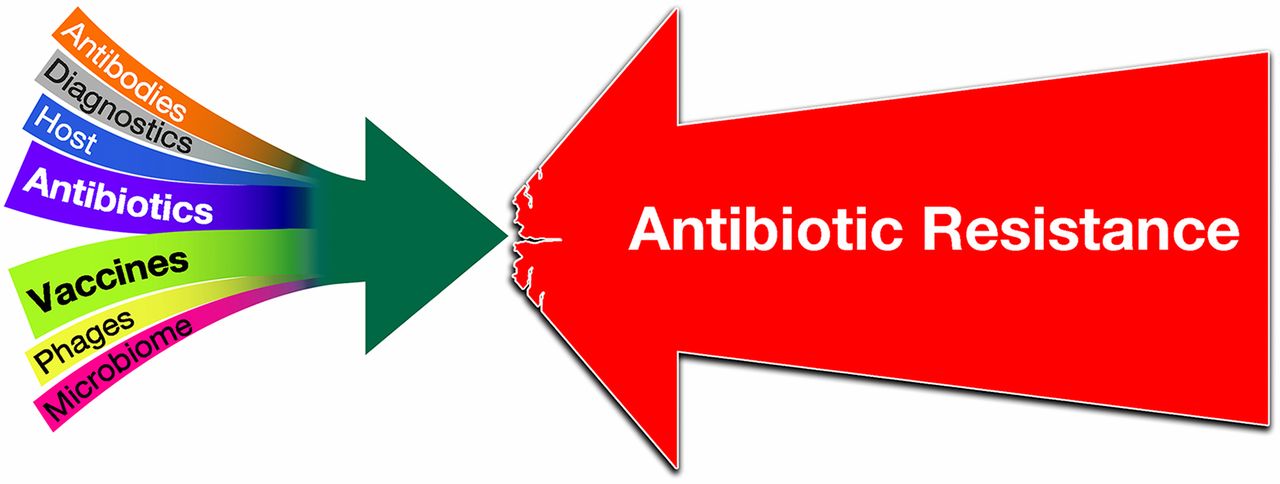

Of great importance, however, is also the development of therapeutic principles that follow different paths than the classical administration of antibiotics. The antimicrobial effect of bacteria destroying viruses, so-called bacteriophages, which was first clinically tested 100 years ago, was largely forgotten in the course of the “antibiotic hype” of Western infection medicine in the 20th century. In Eastern European countries, such as Georgia, this treatment strategy continues to be cultivated and, in view of the impending “poststantibiotic age”, is increasingly becoming the focus of scientific interest again.

The joint project “PhagoFlow” of the consortium partners BwK Berlin, DSMZ and the Fraunhofer-ITEM is one of the research projects that takes up the hypothesis of the antibacterial effect of special viruses and tests their practical applicability in a clinical context.

The book on infectious diseases is therefore still open. Whether we will win the battle against “pestilence” as a synonym for all transmissible diseases a good 90 years after Alexander Fleming’s discovery of the antibacterial effect of penicillin is more uncertain than ever; it also depends on the success of therapeutic strategies “beyond” the antibiotic prescription!